The proposal would establish maximum contaminant levels for PFOA and PFOS, and a hazard index approach for four other PFAS compounds.

On March 14, 2023, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed a federal action to address per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in drinking water, the first in over a decade. If approved, these new National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) will add six contaminants to the list of over 90 existing chemical compounds that are federally regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA).

PFAS compounds were once widely used as water repellants, non-stick surface treatments, and firefighting foams. This EPA ruling would regulate perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), which according to Science Reporter, Bella Isaacs-Thomas, are “two well-studied legacy chemicals that have largely been phased out of use in the United States but linger in the environment and are still used in manufacturing abroad.”

These regulations aim to cap PFOA and PFOS contamination at four parts per trillion (ppt), the lowest level at which they can be reliably measured. It’s worth noting that meeting this standard wasn’t possible in 2016, when the health advisory level was 70 ppt. However, as laboratory technology continues to evolve, water practitioners can detect, measure, and remove contaminants from drinking water better than ever.

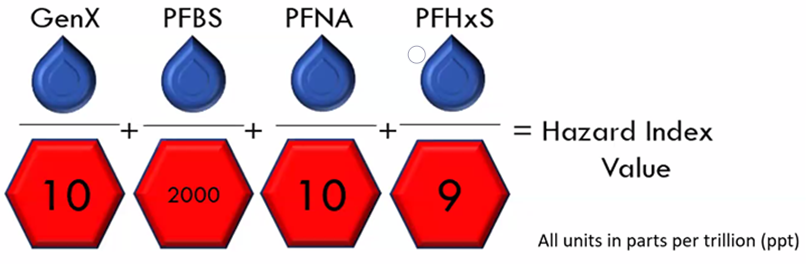

The other four PFAS — perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS), and hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (GenX Chemicals) — would be regulated as a mixture, by testing for each one individually and assessing their risk in combination with one another.

The other four PFAS — perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS), and hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (GenX Chemicals) — would be regulated as a mixture, by testing for each one individually and assessing their risk in combination with one another.

Federal estimates place the number of public drinking water systems requiring treatment upgrades to meet new PFAS maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) between 3,300 and 6,600. That’s nearly 5-10% of the estimated 66,000 public drinking water systems that will need to treat their water to remove PFAS compounds to comply with new SDWA regulations for the six PFAS chemicals.

The EPA anticipates plans to be finalized by the end of 2023, but agencies will have additional time to adjust to these stringent changes. Officials will go through the usual proposal approval process, opening a public comment window after regulations are published to the Federal Register. Regulations won’t take full effect until year three.

As for public water systems in communities with limited resources, the EPA’s increasing involvement in PFAS regulation begs the question, how will they manage compliance costs?

Federal aid funding programs will help small and disadvantage communities redress contaminated drinking water. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law allocates $9 billion towards underserved regions impacted by PFAS and other emerging contaminants. The EPA will direct that money toward water utilities and communities that are on the front lines and are resource-constrained the most.

And as the current administration advocates for EPA’s new budget this year, more resources will be required to combat this pervasive issue.

Local agencies can also access an approximate $12 billion in Drinking Water State Revolving Funds (DWSRF), dedicated to making drinking water safer, and billions more that the federal government has annually provided to fund DWSRF loans — all of which can help communities make important investments in solutions to remove PFAS from drinking water.

Treating the Cause, Not the Effect

The best available technologies to treat for PFAS are Granular Activated Carbon (GAC), Anion Exchange (AIX), Reverse Osmosis (RO), and Nano-filtration (NF). While all of these technologies have shown to be effective in achieving 99% removal and to specifically meet the four ppt proposed MCLs, they are removal technologies that result in contaminant transfer from one media to another rather than complete destruction.

This can be problematic as the EPA has also proposed regulating PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under CERCLA, which may ultimately affect the disposal costs associated with treatment residuals (i.e., spent carbon media, and concentrated waste streams). EPA estimates that disposing of spent treatment media would cost an additional 3-6%.

This can be problematic as the EPA has also proposed regulating PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under CERCLA, which may ultimately affect the disposal costs associated with treatment residuals (i.e., spent carbon media, and concentrated waste streams). EPA estimates that disposing of spent treatment media would cost an additional 3-6%.

The EPA provided a cost-benefit evaluation, comparing the cost of treating the health effects associated with PFAS consumption in drinking water versus the treatment costs, and found that the costs were roughly the same, approximately $1 billion annually. Note that the treatment cost does not consider potential treatment residuals disposal cost increases associated with a change from non-hazardous to hazardous waste.

Although the cost of treating the PFAS in drinking water before it causes health effects is roughly comparable to the costs of treating the health effects themselves, EPA’s proposed regulation is effectively seeking to treat the cause rather than the effect to improve the overall health of the U.S. population served by public water systems.

Key Takeaways

1. The proposal sets numerical standards of four ppt for PFOA and PFOS, a hazard index of one for four GenX Chemicals, and non-enforceable Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLGs) for all six PFAS.

| Compound | Proposed MCLG | Proposed MCL (enforceable levels) |

| PFOA | Zero | 4.0 parts per trillion (also expressed as ng/L) |

| PFOS | Zero | 4.0 ppt |

| PFNA | 1.0 (unitless) Hazard Index |

1.0 (unitless) Hazard Index |

| PFHxS | ||

| PFBS | ||

| HFPO-DA (Commonly referred to as GenX Chemicals) |

*above table from https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas

2. The new PFAS regulations will require additional testing at about 66,000 public water systems, and 5-10% of these systems are expected to require additional treatment to remove PFAS.

3. The Hazard Index considers the different toxicities of GenX Chemicals, PFBS, PFNA, and PFHxS. Water systems would use a hazard index calculation to determine if the combined levels of these PFAS in the drinking water at that system pose a potential risk.

*above table from EPA Proposed PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (March 2023)

4. The MCLs were set at the levels that can “reliably be measured,” but the MCLG is zero, leaving potential for them to get even lower as analytical precision improves.

Authors:

Dawn E. Bockoras | National Director – Environmental Investigation & Remediation | ATLAS

Rik Lantz, P.G., LEED-AP | Senior Consultant, Federal Programs | ATLAS